The Jackal (1997 film)

| The Jackal | |

|---|---|

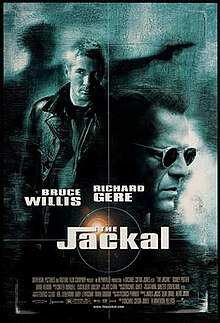

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Michael Caton-Jones |

| Screenplay by | Chuck Pfarrer |

| Story by | Chuck Pfarrer |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Karl Walter Lindenlaub |

| Edited by | Jim Clark |

| Music by | Carter Burwell |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 124 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $60 million[1] |

| Box office | $159.3 million[1] |

The Jackal is a 1997 American action thriller film directed by Michael Caton-Jones. It is a loose take on the 1973 film The Day of the Jackal, which was based on the 1971 novel of the same name by Frederick Forsyth. The film stars Bruce Willis, Richard Gere, and Sidney Poitier in his final theatrically released film role.

The Jackal was released in the United States by Universal Pictures on November 14, 1997. The film received mostly negative reviews from critics but was a commercial success, grossing $159.3 million worldwide against a $60 million budget.

Plot

[edit]A joint operation between the FBI and the MVD in Moscow leads to the killing of the younger brother of Azerbaijani mafia boss Terek Murad. In retaliation, Murad hires a former KGB asset, an international hitman operating under the codename "the Jackal", to assassinate an unidentified prominent American for $70 million. Two weeks later, the MVD capture and interrogate one of Murad's henchmen, Viktor Politovsky, and discover the assassination plot. The interrogation, coupled with recovered documents, leads the FBI and MVD to suspect that FBI Director Donald Brown is the intended target.

Using a series of disguises and stolen or forged IDs, the Jackal prepares for the assassination attempt. FBI Deputy Director Carter Preston and Russian Police Major Valentina Koslova turn to imprisoned IRA sniper Declan Mulqueen for help. They believe that his former lover, a former ETA militant and fugitive named Isabella Zancona, can identify the Jackal. Mulqueen reveals that he knows the Jackal and agrees to help in exchange for his release as well as U.S. citizenship and safe haven for Zancona. Mulqueen and Zancona want revenge on the Jackal after he wounded her in Libya and caused her to miscarry their unborn child. Zancona, now married, provides information to help identify the Jackal, including that he is a United States Army Special Forces veteran with combat experience from his stationing in El Salvador. Zancona discreetly slips Mulqueen a key to a drop box containing a clean passport and $10,000 cash to return to Ireland. However, Preston had earlier warned Mulqueen that if he ever escaped, refused to cooperate, or if an IRA squad tries to rescue him, he would be shot.

Meanwhile, when the Jackal arrives in Montreal to collect a large caliber weapon, a contact notifies him that hijackers are pursuing it. The Jackal kills one hijacker with an extremely poisonous chemical and evades the others. He then hires Ian Lamont, a mechanic and small-time hoodlum, to build a control mount for the weapon. The Jackal demands that all design specs be turned over to him, and he also requires Lamont's complete confidentiality. When Lamont tries extorting more money, the Jackal kills him during a live-fire test of the weapon. The FBI discovers Lamont's remains and evidence that the Jackal intends to utilize a long-range heavy machine gun for the assassination. The Jackal sails across the Great Lakes to Chicago, where he escapes the FBI and almost kills Mulqueen, leading Mulqueen to deduce there is a mole tipping off the Jackal. They discover that the director of the Russian Embassy in Washington, DC, gave the Jackal a direct access code to FBI records, allowing him to track down and kill Koslova and two FBI agents. Before dying, Koslova - passing on a taunt from the Jackal - tells Mulqueen that '[Declan] cannot protect his women'.

As the Jackal drives to Washington, D.C., Mulqueen deduces from the Jackal's mocking statement that his target is not Director Brown, but in fact the First Lady of the United States, who is scheduled to give a public speech. The Jackal, masquerading as a gay man, dates Douglas, a man he encountered earlier in a bar; unbeknownst to Douglas, he uses his garage to store his machine gun. When a news report exposes the Jackal's identity, he kills Douglas. On the date of the First Lady's speech, the weapon is hidden in a minivan parked near the speaker podium, with the Jackal planning to shoot the First Lady via remote control. However, before the Jackal can act, Mulqueen uses a sniper rifle to destroy the weapon's scope and takes off in pursuit of the Jackal, while another marksman blows up the van's fuel tank. The Jackal blindly opens fire before his vehicle is destroyed, and Preston is shot and wounded while tackling the First Lady to safety. Following a chase through the Washington Metro tunnels, Mulqueen confronts the Jackal, who is then shot from behind by Zancona; however, the Jackal's gun discharges a shot, and Mulqueen is also wounded. While Zancona consoles Mulqueen, the severely wounded Jackal pulls a backup gun: seeing this, Mulqueen grabs Zancona's pistol and shoots the killer several times, finally killing him.

A few days later, Preston and Mulqueen witness the Jackal's burial in an unmarked grave. Preston reveals that he is returning to Russia to pursue Terek Murad and his gang. He says that Mulqueen's request to be released was denied, but that he will likely be moved to a minimum security prison. Preston also remarks that his heroics in saving the First Lady have made him "untouchable" within the FBI: knowing his current clout will prevent any backlash against him, he turns his back on Mulqueen, allowing him to go free.

Cast

[edit]- Bruce Willis as The Jackal

- Richard Gere as Declan Joseph Mulqueen

- Sidney Poitier as FBI Deputy Director Carter Preston

- Diane Venora as Major Valentina Koslova, MVD

- Mathilda May as Isabella Celia Zancona

- J. K. Simmons as FBI Agent Timothy I. Witherspoon

- Richard Lineback as FBI Agent McMurphy

- John Cunningham as FBI Director Donald Brown

- Jack Black as Ian Lamont

- Tess Harper as First Lady Emily Cowan

- Leslie Phillips as Woolburton

- Stephen Spinella as Douglas

- Sophie Okonedo as Jamaican Girl

- David Hayman as Terek Murad

- Steve Bassett as George Decker

- Yuri Stepanov as Viktor Politovsky

- Ravil Isyanov as Ghazzi Murad

- Walt MacPherson as Dennehey

- Maggie Castle as Maggie the 13 year old hostage

- Daniel Dae Kim as Akashi

- Michael Caton-Jones as man in Video

- Peter Sullivan as Vasilov

- Richard Cubison as General Belinko

- Serge Houde as Beaufres

- Ewan Bailey as Prison Guard

- Jonathan Aris as Alexander Radzinski

- Edward Fine as Bill Smith

- Larry King as himself

- Murphy Guyer as NSC representative

Production

[edit]The film was in production development from August 19 to November 30, 1996. It was filmed in international locations such as Porvoo, Finland,[2] including its special effects. The film began production titled The Day of the Jackal, but the author of the original novel Frederick Forsyth and the director and producer of the original film Fred Zinnemann and John Woolf opposed the production. They eventually filed an injunction to prevent Universal Pictures from using the name of the original novel and film, and it would be marketed as being "inspired by" rather than directly based on Forsyth's novel.[3][4][5] Edward Fox also reportedly turned down a cameo appearance in the film.[6]

Chuck Pfarrer had written the first script, he was finishing up a three-year deal at Universal when he was offered the project, Pfarrer initially said no, but he agreed to write the script to fulfill contractual obligations to the studio,[7] then Kevin Jarre did a rewrite to Pfarrer's script, contributing the Richard Gere character, Declan Mulqueen, an imprisoned IRA terrorist who strikes up a bargain to assist the FBI.[8] Caton-Jones later said in an interview with The Washington Post that he regretted not being there to supervise and contribute more to the screenplay:

"I never really liked the script. It was always too long, So I was trying to trim it as I went along and I really made the film in the editing room, stripping a lot of excess away".[9]

An early test-screened version of the film had an innocent man shot by Willis' character hiding out in a gay bar. The audience loudly cheered the killing, which came to the attention of GLAAD. Chaz Bono (the group’s entertainment media director) spoke with Jackal producer Sean Daniel, who arranged to have the scene re-edited.[10] Bruce Willis successfully fought to keep a same-sex kiss in the film.[11]

Release

[edit]Home media

[edit]The Jackal was released on VHS, DVD and LaserDisc on April 28, 1998.[12]

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]The Jackal received a 24% rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 33 reviews, with an average rating of 4.6/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "The Jackal is a relatively simple chase thriller incapable of adding thrills or excitement as the plot chugs along."[13] Metacritic gave the film a score of 36 out of 100 based on 20 reviews.[14] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "B−" on an A+ to F scale.[15]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times called it a "glum, curiously flat thriller";[16] he also included the film in his "Worst of 1997", comparing it to the 1973 film and calling it a "retread", "cruder", and "dumbed down".[17] Ruthe Stein of the San Francisco Chronicle called it "more preposterous than thrilling";[18] and Russell Smith of the Austin Chronicle called it "1997's most tedious movie".[19]

At the 1997 Stinkers Bad Movie Awards, Richard Gere received a nomination for Worst Fake Accent, but he lost to Jon Voight for Anaconda and Most Wanted.[20]

Box office

[edit]The Jackal was released on November 14, 1997, with an opening weekend totaling $15,164,595.[21][1] It went on to gross $159,330,280 worldwide, against a $60 million budget.

Music

[edit]The original score for The Jackal was composed by Carter Burwell. It was never officially released on CD, although Burwell uploaded select cues from the film to his website. The project was not a happy experience for Burwell; he disliked the script, and disapproved of producer Danny Saber's remix of his score.[22]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "The Jackal". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- ^ "Post Office action scene - "The Jackal" - Movie Location". Waymarking.com.

- ^ "2nd 'Jackal' raises hackles". Variety. 5 February 1997. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ^ "Helmer takes new shot at 'Jackal'". Variety. 25 September 1997. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ^ "'Jackal' Filmmakers Assail New Film With Classic Title". The Los Angeles Times. 28 October 1996. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ^ "The Day of the Jackal". AFI Catalog. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ "The Screenwriter of SEAL Team 6: An Interview with Chuck Pfarrer by Kent Hill". podcastingthemsoftly.com. 29 November 2016. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ^ "There's Just a Nodding Acquaintance". The Los Angeles Times. 25 October 1997. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ^ "The Jackal and The Running Dogs". The Washington Post. 9 November 1997. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ^ Wolk, Josh (19 November 1997). "Kiss Me Deadly". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 18 August 2020. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ Here Publishing (23 December 1997). "The Advocate". The Advocate: The National Gay & Lesbian Newsmagazine. Here Publishing: 11–. ISSN 0001-8996.

- ^ "'Boogie Nights' comes to video". The Kansas City Star. 3 April 1998. p. 82. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Jackal (1997)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ "The Jackal Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ^ "JACKAL, THE (1997) B-". CinemaScore. Archived from the original on 6 February 2018.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (14 November 1997). "The Jackal". Chicago Sun-Times. Chicago, Illinois: Sun-Times Media. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ Siskel and Ebert: Worst of 1997. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021 – via Youtube.com.

- ^ Stein, Ruthe (14 November 1997). "'Jackal' Can't Hide From Absurd Plot / Willis alters look in mishmash thriller". The San Francisco Chronicle. San Francisco, California: Hearst Corporation. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ Smith, Russell (14 November 1997). "The Jackal". The Austin Chronicle. Austin, Texas: Austin Chronicle Corp. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ "The Stinkers 1997 Ballot". Stinkers Bad Movie Awards. Archived from the original on 18 August 2000.

- ^ "'Jackal' shoots to No. 1 at weekend box office". South Florida Sun-Sentinel. 19 November 1997. p. 69. Archived from the original on 27 November 2022. Retrieved 27 November 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Jackal". Carter Burwell.

External links

[edit]- 1997 films

- 1997 action thriller films

- 1990s American films

- 1990s English-language films

- 1990s political thriller films

- 1990s Russian-language films

- Action film remakes

- American action thriller films

- American political thriller films

- American remakes of British films

- American remakes of French films

- Films about assassinations

- Films about contract killing in the United States

- Films about the Federal Bureau of Investigation

- Films about the Irish Republican Army

- Films about the Russian Mafia

- Films about terrorism in the United States

- Films about The Troubles (Northern Ireland)

- Films based on adaptations

- Films based on British novels

- Films based on works by Frederick Forsyth

- Films directed by Michael Caton-Jones

- Films produced by James Jacks

- Films scored by Carter Burwell

- Films set in Chicago

- Films set in Finland

- Films set in Montreal

- Films set in Moscow

- Films set in Washington, D.C.

- Films shot at Pinewood Studios

- Films shot in Finland

- Gay-related films

- LGBTQ-related film remakes

- LGBTQ-related political films

- Mutual Film Company films

- Political film remakes

- Techno-thriller films

- Thriller film remakes

- Universal Pictures films

- English-language action thriller films